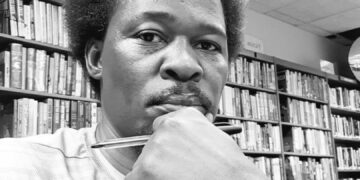

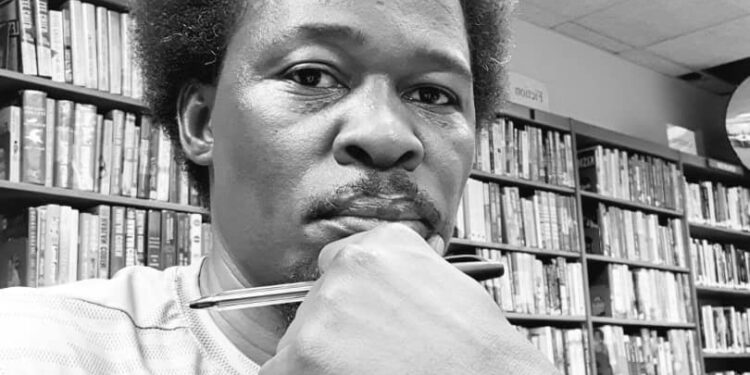

By Gyagenda Semakula Zikusooka Ssajjabbi

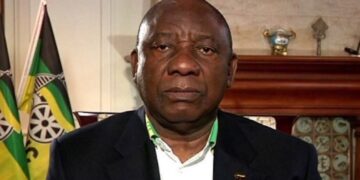

By any historical measure, General Tibuhaburwa Museveni’s rule over Uganda is exceptional. Since clutching power in January 1986 after a five-year guerrilla war, Museveni has governed the country for a whopping four decades, making him one of Africa’s longest-serving leaders. His presidency has shaped Uganda’s political institutions, economic trajectory, and national identity. Yet as time advances, the question of transition and succession has become unavoidable—both for the ruling establishment and for a population where the majority has known no other president.

When Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) came to power, Uganda was emerging from years of instability marked by the regimes of Idi Amin and Milton Obote. Museveni presented himself as a revolutionary reformer, promising democracy and rule of law, security, fight against corruption and economic recovery. In his early years, his government restored relative stability, rebuilt state institutions, and won international praise for economic reforms and pragmatic governance.

However, the political system that evolved over time became increasingly centralized around the imperial presidency. Constitutional changes, most notably the removal of presidential term limits in 2005 and age limits in 2017, effectively reset the clock on Museveni’s tenure and grip on power. These amendments, passed amid political controversy and public protests, signaled a shift from transition as a national project to continuity as a personal one.

The Succession and/or Transition Question That Is Here to Stay

Unlike many countries where leadership change is institutionalized, Uganda’s succession debate remains elusive, unresolved and deeply sensitive. General Museveni has never clearly articulated a succession plan (who comes next?) or an elaborate system of transition (the process from one to another), instead framing continuity as necessary for stability and development. This ambiguity has created political tension within both the ruling party and the opposition. These voices are now louder than ever!

Speculation about a dynastic transition has intensified in recent years, particularly with the rise of Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Museveni’s son and businessman Odrek Rwabwogo (Museveni’s son-in-law). While listening to Radio One’s Spectrum Extra, one of Kenneth Lukwago’s guests expounded on several conspiracy theories of the Chwezi (MK) versus the Balokole (OR) which are the throb and heartbeat of the succession discourse, and have fueled debate about whether Uganda is quietly preparing for a hereditary transfer of power—an idea that clashes with republican principles enshrined in the country’s constitution.

Synchronously, the opposition argues that succession should come through democratic elections rather than elite negotiation (the Mao Way). Repeated election cycles marked by allegations of intimidation, voter apathy, ballot stuffing, commercialization of politics, restrictions on opposition activity, and internet shutdowns have, however, undermined public confidence in electoral transition as a credible pathway.

A Generational Divide

One of the most striking dimensions of Uganda’s transition debate is demographic. Over 75 percent of Ugandans are under the age of 35 (UB40). This generation has no living memory of pre-1986 Uganda (commonly known as the Luweero triangle) and often experiences Museveni’s liberation narrative as distant or imaginative history rather than lived reality. For many young people, the pressing issues are not liberation history or rhetoric but unemployment, skyrocketing living costs, stinking corruption, and political exclusion and persecution of dissents.

This generational disconnect has transformed succession from a theoretical discussion into a social pressure point. I call this the frog in the kettle metaphor as George Barna asserts in his book, “Frog in the Kettle”. Gradual change, unlike abrupt rupture, rarely provokes immediate resistance. Each incremental adjustment–constitutional amendment, expanded security roles in politics, and prolonged incumbency appears manageable in isolation. Over time, however, the cumulative effect reshapes the entire system. The danger lies not in a single decision or issue, but in how slow normalization dulls institutional alarm bells until the system is ill-prepared for inevitable change. Postponing succession in the name of stability and redefining transition as continuity is a recipe for a disorderly transition.

GenZ movements everywhere are increasingly framing transition not merely as a change of leadership, but as a redefinition of governance toward accountability, opportunity, and inclusion.

Stability versus Renewal

Supporters of General Museveni and his ruling party argue that his continued leadership guarantees stability in a region often marked by conflict. Yes, Uganda’s role in regional security, peacekeeping missions on the continent, and counter-terrorism is frequently cited as justification for continuity. From this perspective, an abrupt or poorly managed transition could risk political instability or institutional collapse.

Conversely, regime critics counter that prolonged rule itself creates fragility. They argue that when power becomes personalized, institutions weaken, and uncertainty increases around what happens when leadership eventually changes. In this view, a managed, constitutional transition is not a threat to stability but a safeguard against future crisis.

As Ugandans brace themselves for the seventh term of Gen Tibuhaburwa, the country stands at a defining moment; the crossroad.

Transition and succession are no longer abstract debates but central questions shaping political discourse, civic engagement, and international perceptions. Whether Uganda’s next chapter is written through deliberate reform or forced by circumstance will depend largely on what will transpire after now.

What is evidently clear is that Gen Museveni’s legacy will not be judged solely by how long he ruled, but by whether the country he superintended over for almost half a century ultimately emerged with resilient institutions capable of outliving him as an individual. The transition question, long deferred, remains the ultimate test of that legacy.

The writer is a Journalist, Lawyer, Church Minister